An excerpt from my book

BRITISH INVASION '64

Published in 2023 by BearManor Media

It's

tempting to say that Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were destined to make music

together. They met as seven-year-olds in

the same classroom and were close friends for the next four years until Michael

(as Mick was then known) and Keith moved on to different schools, and lost

contact with one another. Seven years

after that, in 1961, the two 18-year-olds found themselves waiting on the same

train platform, sort of recognizing one another, but neither making the effort

to reintroduce himself. But then,

Richards noticed Jagger was carrying record albums by Chuck Berry and Muddy

Waters and was astonished; he didn’t know anyone else who loved the Chess

Chicago blues musicians the way he did.

The two young men then began talking in earnest, and each discovered

that the other was no dilettante fan . . . they were both serious devotees in

their love of American R&B and the blues.

Soon

enough Keith (who played guitar) and Mick (who sang) began jamming with other

friends, and it wasn’t long before the duo and their new roommate,

multi-instrumentalist Brian Jones, found their way into Alexis Korner’s Blues

Incorporated, and began playing London clubs.

A few months later, Jones was looking to form his own blues group, and

while Jagger and Richards weren’t initially on his list of people to join his

band, they more or less fell into it soon enough. Pressed for a name for their group, Jones

glanced at the Muddy Waters record he was holding in his hands, and he saw a

song title that appealed to him. “We’re

the Rollin’ Stones,” he proclaimed to the world.

They

began woodshedding in clubs throughout England, and by early ’63 the classic

line-up . . . Jagger, Richards, Jones, bassist Bill Wyman, and drummer Charlie

Watts . . . had set. A residency at

London’s Crawdaddy Club generated buzz about the Stones being a powerful live

act, and they soon attracted the attention of Andrew Loog Oldham. Perhaps best described as equal parts

wunderkind and hustler, Oldham was only 19 years old in 1963 (younger than any

member of the Stones, in fact), but he had already established himself as a

freelance rock music publicist, having worked for the Beatles, as well as

handing the promotions for American folk artist Bob Dylan when he came to the

UK earlier that year. The Beatles had taken

a shine to the young go-getter and encouraged him to pursue his interest in

managing a band. By many accounts, it

was the Beatles themselves who suggested that Oldham go and see the Rolling

Stones, whom the Fab Four had already met, and enjoyed attending their shows at

the Crawdaddy. Catching one of their

performances that May, Oldham immediately saw the potential for the group to be

a huge success, and he convinced them to let him be their manager.

Working

tirelessly, Oldham launched a one-man marketing campaign that elevated the

reputation of the Stones in London, and quickly brought them to the attention

of Decca Records. Their debut single that summer, a cover of

Chuck Berry’s “Come On”, made it to a respectable #21 in the UK.

A

chance meeting between Lennon, McCartney, Jagger, and Richards, as both duos

passed one another on a London sidewalk, led to a suggestion by Lennon that he

and his songwriting partner had a half-finished tune that he thought would

sound great if done by the Stones.

Repairing to a nearby pub, John and Paul put the finishing touches on a

Bo Diddly beat number called “I Wanna Be Your Man”. The two Stones happily accepted it, rushed

into the studio, and the band made it to #12 on the chart with the song.

Having

observed that Lennon and McCartney must certainly be earning a fair deal of

money from their songwriting, Jagger suggested that the band try working on

some original material as well. The

result was an instrumental dubbed “Stoned”, which was the B-side to their

second single. Rather than list all the

band members’ names as the songwriters, the tune was credited to the pseudonymous

“Nanker Phelge”, a nom de plume which would be employed in the future for songs

that were not written solely by Jagger and Richards.

To

hype his band, Oldham promoted them as the “Anti-Beatles” (a tactic which the

Beatles themselves found amusing, and which they happily encouraged.) Noted journalist and author Tom Wolfe best

described the public personas of the two bands thus: “The Beatles want to hold

your hand, but the Rolling Stones want to burn down your town.” And while Brian Jones and Keith Richards could be considered

heartthrobs, the band on the whole were deemed fairly unattractive by pop music

standards . . . which is precisely what they wanted. The group’s very lack of conventional good

looks was a key to their image as “bad boys”.

As one female fan (speaking for many) gushed, “They’re so ugly, they’re

beautiful!”

The 'anonymous advertiser' of this magazine ad was almost certainly Andrew Loog Oldham

Not

quite ready to place a self-penned song on their next A-side yet, their cover

of Buddy Holly’s “Not Fade Away” was their next release, and it took them into

the British Top Five. Significantly, it

skirted close that spring to the American Top 40, which prompted Oldham to book

a brief US tour for his band for June.

Upon

their arrival in New York City, they were met by 500 screaming girls . . . a

significant number of whom had allegedly been hired by Oldham to give his band

a Beatles-level welcome to America. Also hired was New York disc jockey Murray

“the K” Kaufman, the self-declared “Fifth Beatle”, who was joined at the hip to

the Stones during their stay in the city so as to show them around town, gin up

press coverage, and have them guest on his radio show. The bandmembers found Murray tackily tedious,

but there was one good thing that came from their compulsory affiliation: they

heard him play a new R&B song by the Valentinos (a.k.a. Bobby Womack and

his brothers), “It’s All Over Now”, and the band decided to cover it for their

next album.

Their

tour kicked off, appropriately enough, in San Bernadino, California, which is

the final stop name-checked in “Route 66”, a song which the Stones loved and

covered on their first album. This

initial show set the pace for a tour often fraught with mishaps and hostility,

as a young man was able to relieve a police officer of his pistol during the

concert and fired it at the stage, narrowly missing Jagger before the assailant

was wrestled to the ground! Next, in San

Antonio, the Stones found themselves booked for four performances at the Texas

Teen Fair, alongside such acts as Country & Western star George Jones, as

well as the Marquis Chimps. Backstage,

Keith Richards and Bill Wyman got into an angry confrontation with some

disapproving cowboys, and afterward the two young Englishmen promptly went to a

sporting goods store and purchased handguns for themselves, since local police

were proving to be inept at providing them with proper protection.

Next

came the undisputed highlight of the American visit, as the Stones arrived in

Chicago (where, unfathomably, Oldham had not booked any concerts for

them). There, they spent a full day in

the heart of Chicago blues, the Chess Records studio, where they recorded no

fewer than six songs (including “It’s All Over Now”), and in between numbers

they downed copious amounts of whiskey with their heroes, Muddy Waters and

Chuck Berry. The latter was particularly

pleased that the Rolling Stones were cutting one of his songs on this day,

“Around and Around”, as he had begun receiving royalty checks for his compositions

that were covered by the Beatles and other British acts and was always happy to

add to the tally.

Back

on the road days later, the group played Excelsior, Minnesota; Omaha, Nebraska;

Detroit, Michigan (where the local promoter bungled things so badly, there were

less than 500 paying fans in a 14,000 seat arena); Pittsburgh and Harrisburg in

Pennsylvania; and then finally back to New York City for two shows at Carnegie

Hall (which, between hosting the Rolling Stones, the Beatles, and the Dave

Clark Five on stage in 1964, was making the venerable old venue as well known

to the younger set for rock and roll as it was to elder generations for

classical and jazz music). By the end of

their third week in America, the Stones were glad to be headed back home at

last. But if the touring was not always

enjoyable, they did have the happy experience of recording at Chess.

Yet

there was also a bit of a controversy which flared up amid the tour. Shortly after first arriving in California,

the Stones made their US national television debut on ABC’s The Hollywood

Palace. Similar in format to The

Ed Sullivan Show, the Palace featured a variety of acts each week,

from dancers and comedians to circus acrobats and . . . increasingly . . . rock

and roll bands. Unlike the rival show

over on CBS, this one had a different host each week. For the episode which aired on June the 6th,

the host was singer and actor Dean Martin.

The controversy erupted over the tenor of the jokes which were written

for Martin to deliver when introducing the Rolling Stones. Although fairly innocuous (“I’ve been rolled

when I was stoned myself” played into Martin’s on-stage drunkard persona; “You

know all these new groups today, you’re under the impression they have long

hair . . . not true at all, it’s an optical illusion. They just have low foreheads and high

eyebrows” is a joke that could have been applied to virtually any of the

British bands), Martin seemed to reveal some personal condescension when, after

the band’s set, the host turned to the camera and blandly said, “Aren’t they

great?” and rolled his eyes upward.

As

uproars go, this was a relative tempest in a teapot. But it exposed division along generational

lines, as teens saw it as a mean-spirited attack on what they cared for, and

their parents tended to find it as a funny denunciation of these ridiculous

longhaired so-called ‘musicians’. The

divide would only widen in the years to come.

And in the meantime, Andrew Loog Oldham could only delight in the

publicity it generated.

However,

there was one more positive event that took place during the band’s sojourn to

America. London Records, Decca’s

American subsidiary, took it upon itself to try and bolster the chart power of

the Rolling Stones in the US, so they selected a song from the group’s debut

album, “Tell Me” (the very first Jagger/Richards-penned tune to be recorded),

and put it out. It instantly attracted

airplay, and within a few weeks it peaked at #24, the first appearance in the

American Top 40 by the Stones.

A

mere two weeks after London released “Tell Me”, Decca rush-released “It’s All

Over Now” from the Chess session as the group’s next worldwide single. It was their first Number One in the UK, and

a big hit in several other countries, but it only made it to #26 in America . .

. perhaps because it was competing for airplay that summer with “Tell Me”. Still, it gave the Rolling Stones two

concurrent Top 30 hits in the US and set the stage for greater success to come.

Bedraggled

and somewhat disillusioned with America, the Stones returned to Britain, but

perhaps with the satisfaction of knowing they had left discord, bewilderment,

and mania in their wake; all-in-all, the Rolling Stones’ manifesto writ large.

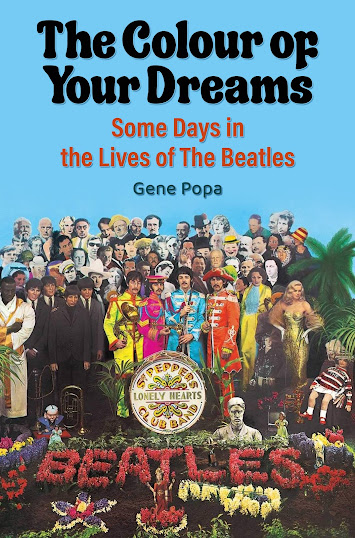

BRITISH INVASION '64 is available at Amazon.com and BarnesandNoble.com, or may be ordered from your local bookseller from BearManorMedia.com